A climate housing bubble threatens to erode real estate prices in much of the U.S. in the coming years, posing particular challenges for low-income residents, a new study finds, Andrew writes.

Why it matters: With more severe and frequent extreme weather events, the resilience of homeowners and communities is on the line.

How lenders, insurance companies and others incorporate escalating flood risks into property prices is a key question facing at-risk communities.

Zoom in: The study, published Thursday in Nature Climate Change, finds that nationally, property prices are currently overvalued by between $121 billion and $237 billion, when compared to their actual flood risk.

The current prices mask the true danger that these properties are exposed to, because of factors such as outdated FEMA flood maps, incentives in the National Flood Insurance Program and home buyers who lack climate change information.

The paper is the result of a collaboration between experts at the Environmental Defense Fund, First Street Foundation, Resources for the Future, the Federal Reserve and two universities.

Scientists relied on First Street’s updated modeling that simulates rainfall-induced, or pluvial flooding, as well as coastal flood events.

Between the lines: The authors found that right now, 14.6 million properties face at least a 1% annual probability of flooding, putting them in the so-called 100-year flood zone.

However, this is expected to increase by 11% in a mid-range emissions scenario, with average annual losses spiking by at least 26% by 2050.

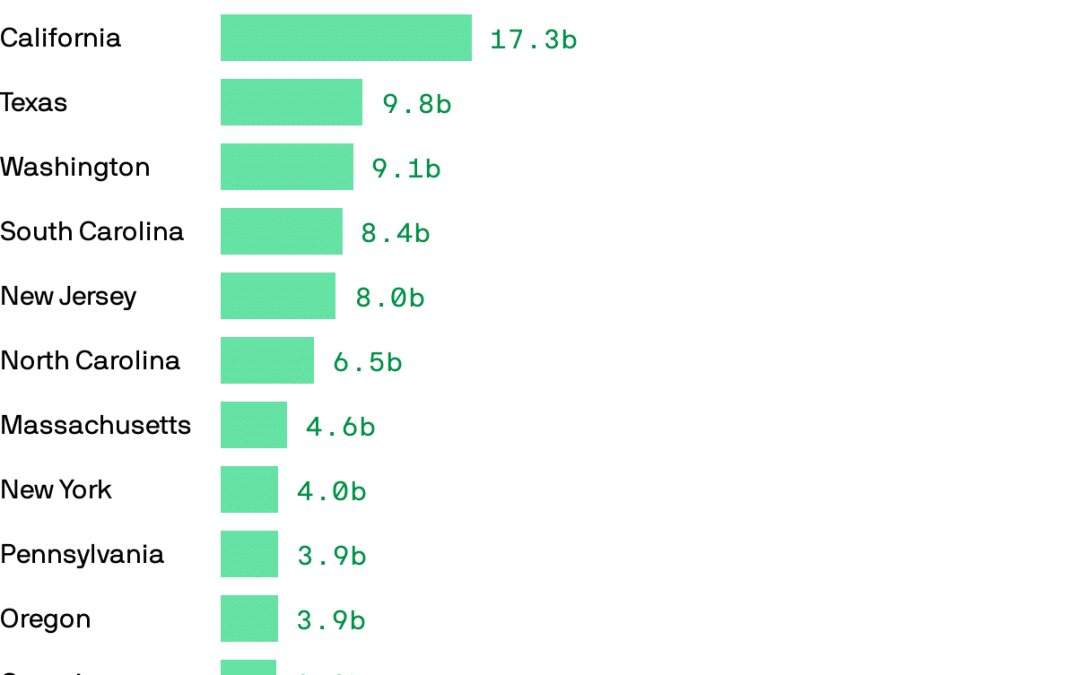

In dollar terms, the areas with the greatest property overvaluations are along the coasts, where there is overlap between rising seas, fewer flood disclosure laws, and a high number of residents who may not view climate change as a near-term threat.

Much of the overvaluation comes from vulnerable properties located outside of FEMA’s 100-year flood zone.

Once the higher flood risks become evident, homeowners will lose equity in their property, which is a particular threat to lower-income homeowners.

What they’re saying: “There is a significant amount of ‘unknown’ flood risk across the country based solely on the differences in the publicly available federal flood maps and the reality of actual flood risk,” Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications at First Street Foundation, said in a statement.